三位IMF经济学家周四发文呼吁,各国政府需要重新考虑财政紧缩和对外资开放的价值。文章一出,立即引发轩然大波。因为IMF正是当年力推这些政策的重要参与机构之一。

IMF总裁拉加德

在IMF最新一期刊物《FINANCE & DEVELOPMENT》上发表的题为《新自由主义:已超卖》(Neoliberalism: Oversold ?)的论文中,IMF研究部副主任Jonathan D. Ostry、宏观经济发展部主管Prakash Loungani等三位经济学家对“新自由主义”提出了批评。

“新自由主义”的政策理念,其以1989年诞生的“华盛顿共识”为政策宣言。后者是一整套针对当时陷入危机的拉美国家和东欧转轨国家的政治经济理论,提出者是美国,参与者为IMF、世界银行、美洲开发银行和美国财政部的研究人员。

“华盛顿共识”主要包括压缩财政赤字、重视基建、降低边际税率、实施利率市场化、采用具有竞争力的汇率制度、实施贸易自由化、放松对外资的限制、实施国有企业私有化等十大方面。

这种政策在近几年的希腊危机期间被IMF通过借钱而强加给希腊推行。如今,它是美国总统竞选中的热门话题之一。

新自由主义的精神领袖、著名经济学家弗里德里希·哈耶克

上述三位IMF经济学家对新自由主义理论的批评之处主要集中在两点:一是财政紧缩政策,二是不同国家之间的资本自由流动。

他们援引全球数据称,上述两个关键政策不仅扩大了社会不平等,还危害了经济的持续增长,也令资本市场不稳定。

具体细节方面,三位经济学家称,财政紧缩方面,他们认同部分欧洲国家由于无法不断借贷度日,在别无选择的情况下只能紧缩开支,但不应该要求所有国家都一刀切,统统采取财政紧缩措施。对于有良好记录的国家来说,减少债务的好处其实很小,但是加税及削减开支的代价却很大。

文章还称,对于一个国家来说,债务负担是已经发生且无法恢复的沉没成本。有充足的财政空间的政府应当选择保持一定的债务水平以推动经济发展,而不是强行增加盈余来减少债务。

他们还表示,新自由主义提倡的金融贸易自由化当中,资本流入的确有助于经济发展,比如外商直接投资。但证券投资及债务类资金流入却对一个国家的经济发展没有帮助。

同时,开放资本账户等金融市场化手段则会导致经济波动加剧,令金融危机更加频繁。也有研究显示这与社会不平等有关。有足够证据显示,开放资本流动需要付出庞大代价。

文章还强调,无论是开放资本流动或是推动紧缩政策,都会导致社会收入不均问题加剧,从而阻碍经济发展。

事实上,新自由主义在过去多年一直引发学界和政界争议,IMF也曾对此进行反思。比如,该机构前首席经济学家Olivier Blanchard早在2010年已指出,很多发达经济体都不应强推紧缩,而是要作中期的财政整顿。

附:IMF经济学家原文《新自由主义已然江郎才尽?》(翻译来自微信公众号“女神读书会”)

Neoliberalism: Oversold?

新自由主义已然江郎才尽?

Instead of delivering growth, some neoliberal policies have increasedinequality, in turn jeopardizing durable expansion

部分新自由主义的政策并没有给经济带来增长,反而加剧了不公平,进而危及了经济体量的持久扩大。

Milton Friedman in 1982 hailed Chile as an “economic miracle.” Nearly adecade earlier, Chile had turned to policies that have since been widelyemulated across the globe. The neoliberal agenda—a label used more by critics than by the architects of the policies—rests on two main planks. The first is increased competition—achieved through deregulation and the opening up of domesticmarkets, including financial markets, to foreign competition. The second is asmaller role for the state, achieved through privatization and limits on theability of governments to run fiscal deficits and accumulate debt.

1982年弥尔顿·弗里德曼盛赞智利是一个“经济奇迹”。将近十年前,智利已转向那些被世界各地广泛效仿的政策。“新自由主义议程”这一标签主要被批评者拿来使用,而非那些政策缔造者们,它主要基于两条总纲。第一点是加剧竞争,这可以通过放松管制和开放国内市场迎接外资竞争,包括开放金融市场来实现。第二点是弱化国家的作用,通过私有化和限制各国政府的运行财政赤字和债务积累的能力来实现。

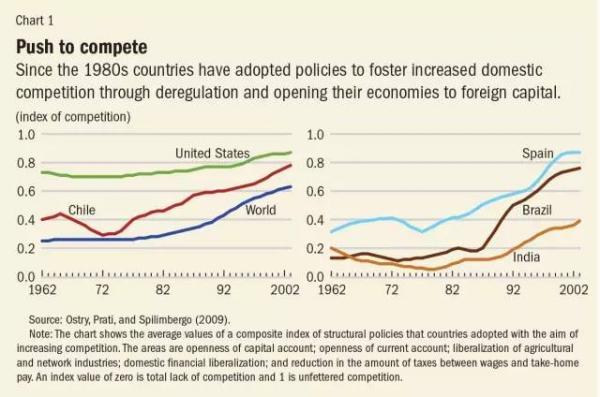

There has beena strong and widespread global trend toward neoliberalism since the 1980s,according to a composite index that measures the extent to which countriesintroduced competition in various spheres of economic activity to fostereconomic growth. As shown in the left panel of Chart 1, Chile’s push started a decade or so earlier than 1982, with subsequent policy changes bringing it ever closer to theUnited States. Other countries have also steadily implemented neoliberalpolicies (see Chart 1, right panel

自20世纪80年代以来,全球范围内出现了一个强大的新自由主义趋势,这是一个综合指数以后得出的结论,该指数用于测量各个国家为了促进经济增长的在多个领域的经济活动中的程度。如图1的左图中所示,早在1982年之前,智利推行新自由主义已有10年左右了。随后的政策变化使其比以往任何时候都要接近于美国。其他国家也稳步实施新自由主义政策(见下图)。

There is much to cheer in the neoliberal agenda. The expansion ofglobal trade has rescued millions from abject poverty. Foreign directinvestment has often been a way to transfer technology and know-how todeveloping economies. Privatization of state-owned enterprises has in manyinstances led to more efficient provision of services and lowered the fiscalburden on governments.

“新自由主义议程”得到了许多呼声。全球贸易的扩张已经从赤贫中救出了数百万人。外国直接投资也成了将科技和知识技能转移到发展中国家经济体的一种常见方式。许多时候,国有企业的私有化使得服务的供应更高效,并降低各国政府财政负担。

However, there are aspects of the neoliberal agenda that have notdelivered as expected. Our assessment of the agenda is confined to the effectsof two policies: removing restrictions on the movement of capital across acountry’s borders (so-calledcapital account liberalization); and fiscal consolidation, sometimes called “austerity,” which isshorthand for policies to reduce fiscal deficits and debt levels. An assessmentof these specific policies (rather than the broad neoliberal agenda)reaches three disquieting conclusions:

•The benefits in terms of increased growth seemfairly difficult to establish when looking at a broad group of countries.

•The costs in terms of increased inequality areprominent. Such costs epitomize the trade-off between the growth and equityeffects of some aspects of the neoliberal agenda.

•Increased inequality in turn hurts the level and sustainability ofgrowth. Even if growth is the sole or main purpose of the neoliberal agenda,advocates of that agenda still need to pay attention to the distributionaleffects.

不过在一些方面,“新自由主义议程”并没有如期实现。我们对此“议程”的评估仅限于两项政策的效果:一、消除资本在国家间的流动限制(所谓的资本账户自由化)。二、财政整合,有时也被称为“紧缩”,这是减少财政赤字和债务水平的政策的简称。对于这些具体政策(而不是广义的“新自由主义议程”)的评估有三点令人不安的结论:

•在一个更加广泛的、多国团体的视域下来看(译者按:如欧盟),利益增长似乎很难实现。

•不公平的加剧非常显著。这样的代价体现了新自由主义议程的某些方面对经济增长和公平效益之间的权衡。

•不平等的加剧进而损害了经济增长的水平和可持续性。即使增长是新自由主义议程的唯一或主要目的,该议程的倡导者还需要注意的分配的结果。

Open and shut?

As Maurice Obstfeld (1998) has noted, “economic theory leaves no doubt about the potential advantages” of capital account liberalization, which is also sometimes calledfinancial openness. It can allow the international capital market to channelworld savings to their most productive uses across the globe. Developingeconomies with little capital can borrow to finance investment, therebypromoting their economic growth without requiring sharp increases in their ownsaving. But Obstfeld also pointed to the “genuine hazards” of openness toforeign financial flows and concluded that “this duality of benefits and risks is inescapable in the real world.”

开放还是关闭?

正如莫里斯·奥布斯特菲尔德(1998年)所指出的,“经济理论绝不怀疑潜在优势”这是对资本账户自由化来说的,它有时也被称为金融开放。它可以让国际资本市场打开渠道,从而使世界上的储蓄最大程度上被利用。发展中国家资本有限,可以借贷进行经济投资,促进其经济增长,而不需要使自己的储蓄急剧增加。但奥布斯特菲尔德还指出了开放外国资本流动的“真正风险”,并认为“这种收益和风险并存的二元性在现实世界中是无法避免的。”

This indeed turns out to be the case. The link between financialopenness and economic growth is complex. Some capital inflows, such as foreigndirect investment—which may include atransfer of technology or human capital—do seem to boost long-term growth. But the impact of other flows—such as portfolio investment and banking and especially hot, orspeculative, debt inflows—seem neither toboost growth nor allow the country to better share risks with its tradingpartners (Dell’Ariccia and others,2008; Ostry, Prati, and Spilimbergo, 2009). This suggests that the growth andrisk-sharing benefits of capital flows depend on which type of flow is beingconsidered; it may also depend on the nature of supporting institutions andpolicies.

情况也的确如此。资本开放与经济增长之间的关系非常复杂。一些资本流入,如外商直接投资,其中可能包括科技或人力资本的转移,似乎能刺激长期的经济增长。但其他方面资本的流入,如尤为火爆的证券投资和银行投资,或投机性的债务流入,似乎既不刺激经济增长,也无法使该国与贸易伙伴更好地共担风险(Dell’Ariccia等人,2008年;Ostry,Prati和的Spilimbergo,2009)。这表明,经济增长和资本流动带来的风险共担型的利益取决于流动类型,也可能取决于配套制度和政策的性质。

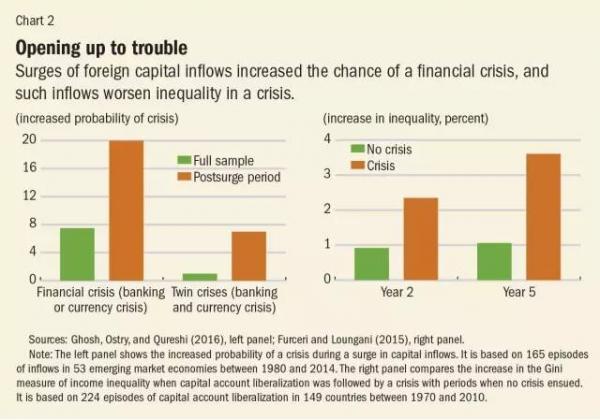

Although growth benefits are uncertain, costs in terms of increasedeconomic volatility and crisis frequency seem more evident. Since 1980, therehave been about 150 episodes of surges in capital inflows in more than 50emerging market economies; as shown in the left panel of Chart 2, about 20percent of the time, these episodes end in a financial crisis, and many ofthese crises are associated with large output declines (Ghosh, Ostry, andQureshi, 2016).

尽管在获益方面不是很确定,但经济动荡和危机频率加剧这两个方面倒是变得更加明显。自1980年以来,在50多个新兴市场经济体中。已经有大约150次危机事件由资本流入导致。如图2的左图中所示,这段时间大约有20%的事件以金融危机告终,许多这些危机都与产出大量下降有关(戈什,奥斯特里,和库雷希,2016年)。

The pervasiveness of booms and busts gives credence to the claim byHarvard economist Dani Rodrik that these “are hardly a sideshow or a minor blemish in international capitalflows; they are the main story.” While thereare many drivers, increased capital account openness consistently figures as arisk factor in these cycles. In addition to raising the odds of a crash,financial openness has distributional effects, appreciably raising inequality(see Furceri and Loungani, 2015, for a discussion of the channels through whichthis operates). Moreover, the effects of openness on inequality are much higherwhen a crash ensues (Chart 2, right panel).

大面积的繁荣与大面积的萧条(如此大起大落)让哈佛大学经济学家,丹尼·罗德里克得以断言,这些事件“不是在国际资本流动中的一个插曲或是小瑕疵,它们正是主要情节。”有了如此多先例,坚持加大资本账户开放被证明在这个循环中是一个风险因素。除了提高崩溃的几率,资本开放还具有分配效应,即明显加剧不公平(见Furceri和Loungani,2015年,对于此类运作渠道的讨论)。此外,当经济崩溃来临,开放带来的不公平效应将会更大。(见下图)。

The mounting evidence on the high cost-to-benefitratio of capital account openness, particularly with respect toshort-term flows, led the IMF’s former FirstDeputy Managing Director, Stanley Fischer, now the vice chair of the U.S.Federal Reserve Board, to exclaim recently: “What useful purpose is served by short-term international capitalflows?” Among policymakerstoday, there is increased acceptance of controls to limit short-term debt flowsthat are viewed as likely to lead to—or compound—a financialcrisis. While not the only tool available—exchange rate and financial policies can also help—capital controls are a viable, and sometimes the only, option whenthe source of an unsustainable credit boom is direct borrowing from abroad(Ostry and others, 2012).

资本账户开放,特别是对于短期流动来说,“成本-效益”的转化率很高,越来越多的证据表明了这一点。这让国际货币基金组织(IMF)的前第一副理事,现美联储委员会的副主席,斯坦利·费希尔,最近惊呼:“短期国际资本流动有何益处?”今天,政策制定者们,更加倾向控制政策,以限制短期债务流动,因为它往往直接导致或者催化经济危机。虽然资本控制不是仅有的有效手段,汇率和财政政策也会起作用,但它是非常靠谱的,甚至当一股当不可持续的信贷繁荣的来源是直接借用海外资本时,它是唯一的手段。(奥斯特里等,2012)

Size of the state

Curbing the size of the state is another aspect of the neoliberalagenda. Privatization of some government functions is one way to achieve this.Another is to constrain government spending through limits on the size offiscal deficits and on the ability of governments to accumulate debt. Theeconomic history of recent decades offers many examples of such curbs, such asthe limit of 60 percent of GDP set for countries to join the euro area (one ofthe so-called Maastricht criteria).

政府的规模

遏制政府的大小是新自由主义议程的另一个方面。一些政府职能私有化是实现这一目标的途径之一。另一种是通过限制财政赤字的规模和政府债务累积的能力来控制政府开支。近几十年来的经济发展史提供了很多此类限制的例子,比如加入欧元区国家的,赤字不得超过GDP的60%的限定(所谓的马斯特里赫特标准之一)。

经济学理论很少提供对最佳公共债务目标的指导。一些理论表明需要更高的债务(因为税收具有扭曲性),而另一些则认为是更低的甚至是负的水平(因为应对不利冲击需要预防性储蓄)。在一些财政政策的建议中,IMF主要关注各国政府减少赤字和债务水平的步伐,这是全球金融危机背景下,由发达经济体的债务积累所引起的:步伐太慢会使市场失去勇气;太快则会破坏复苏。但IMF也同意,中期就偿还部分债务,降低一些负债率,尤其是一些有广泛的发达国家和新兴国家参与债务里,主要是作为对未来冲击的保险。

But is there really a defensible case for countries like Germany,the United Kingdom, or the United States to pay down the public debt? Twoarguments are usually made in support of paying down the debt in countries withample fiscal space—that is, incountries where there is little real prospect of a fiscal crisis. The first isthat, although large adverse shocks such as the Great Depression of the 1930sor the global financial crisis of the past decade occur rarely, when they do,it is helpful to have used the quiet times to pay down the debt. The secondargument rests on the notion that high debt is bad for growth—and, therefore, to lay a firm foundation for growth, paying down thedebt is essential.

但其他国家真的能像德国,英国,或美国一样能守住危机,来偿还公共债务?通常有两个理由来支持国家是否有拥有偿还债务的充足财政空间,这意味着那些国家几乎不会出现财政危机。第一点,虽然像20世纪30年代的大萧条或过去十年的全球性金融危机那样的巨大负面冲击很少发生,但在平稳时期偿还债务是有所助益的。第二个理由是建立在“高负债不利于经济发展”这一概念之上的,因此,偿还债务能为发展打下一个坚实的基础。

It is surely the case that many countries (such as those in southernEurope) have little choice but to engage in fiscal consolidation, becausemarkets will not allow them to continue borrowing. But the need forconsolidation in some countries does not mean all countries—at least in this case, caution about “one size fits all” seemscompletely warranted. Markets generally attach very low probabilities of a debtcrisis to countries that have a strong record of being fiscally responsible(Mendoza and Ostry, 2007). Such a track record gives them latitude to decidenot to raise taxes or cut productive spending when the debt level is high(Ostry and others, 2010; Ghosh and others, 2013). And for countries with astrong track record, the benefit of debt reduction, in terms of insuranceagainst a future fiscal crisis, turns out to be remarkably small, even at veryhigh levels of debt to GDP. For example, moving from a debt ratio of 120percent of GDP to 100 percent of GDP over a few years buys the country verylittle in terms of reduced crisis risk (Baldacci and others, 2011).

无疑许多国家(如那些在欧洲南部的国家)别无他法,只能选择财政整合。因为市场不会允许他们继续借贷。但一些国家需要整合并不意味着所有国家需要——至少在这种情况下,关于“一刀切”警告似乎是必要的。市场通常认为那些有较好财政责任记录的国家,债务危机的可能性会低一些(门多萨和奥斯特里,2007)。这样的跟踪纪录给了他们一个标准,当这些国家债务水平较高时,决定不提高税收或削减生产开支。(奥斯特里等,2010; Ghosh等,2013年)。而对于具有较强的跟踪记录的国家,减债是应对未来财政危机的保险,其好处真可谓是非常小,即使债务占GDP比重很高。例如,从债务比率占GDP的120%从几年内变到100%,这对国家降低危机风险并没有多大作用。(巴达西等,2011年)

But even if the insurance benefit is small, it may still be worthincurring if the cost is sufficiently low. It turns out, however, that the costcould be large—much larger than thebenefit. The reason is that, to get to a lower debt level, taxes that distorteconomic behavior need to be raised temporarily or productive spending needs tobe cut—or both. The costs of the tax increases or expenditure cuts requiredto bring down the debt may be much larger than the reduced crisis riskengendered by the lower debt(Ostry,Ghosh, and Espinoza, 2015). This is not to deny that high debt is bad forgrowth and welfare. It is. But the key point is that the welfare cost from thehigher debt (the so-called burden of the debt) is one that has already beenincurred and cannot be recovered; it is a sunk cost. Faced with a choicebetween living with the higher debt—allowing the debt ratio to decline organically through growth—or deliberately running budgetary surpluses to reduce the debt,governments with ample fiscal space will do better by living with the debt.

但是,即使保险金很少,如果成本足够低,它可能仍然是值得承担。然而,事实证明,这种成本比获益大得多。其原因在于,要获得较低的债务水平,税(即扭曲经济行为)需要暂时升高或生产性开支需要被削减,甚至两者同时进行。而加税或削减开支来被用来降低债务,但其费用可能比用低债务降低的危机风险大得多(奥斯特里,戈什和埃斯皮诺萨,2015)。这并不是否认高负债不利于增长和福利。高负债确实不好。但关键是,高债务下的福利成本(所谓的债务负担)是已经发生且无法收回的成本之一,它是一种沉没成本。与高额债务共存,使债务比率在经济增长中有机下降,或者刻意以预算盈余来减少债务,面对这两种选择时,只有与债务共存,拥有充足的财政空间的政府才能有更好的表现。

Austerity policies not only generate substantial welfare costs dueto supply-side channels, they also hurt demand—and thus worsen employment and unemployment. The notion that fiscalconsolidations can be expansionary (that is, raise output and employment), inpart by raising private sector confidence and investment, has been championedby, among others, Harvard economist Alberto Alesina in the academic world andby former European Central Bank President Jean-Claude Trichet in the policyarena. However, in practice, episodesof fiscal consolidation have been followed, on average, by drops rather than byexpansions in output. On average, a consolidation of 1 percent of GDP increasesthe long-term unemployment rate by 0.6 percentage point and raises by 1.5percent within five years the Gini measure of income inequality (Ball andothers, 2013).

紧缩政策不仅因供应方的渠道而产生巨大的福利成本,同样也伤害了需求,从而恶化就业。财政整合可以是扩张性(即提高产出和就业)的,某种程度上是通过提高私营部门的信心和投资来实现的。这一观点在学术界被哈佛大学经济学家阿尔贝托·阿莱西以及其他人所认同,在政策领域,则被前欧洲央行(ECB)主席Jean-Claude Trichet认同,然而,在实践中,财政整合的意外也随之而来,这通常是产量降低而非扩张。一般而言,1%GDP的合并增加了0.6个百分点的长期失业率,并且,用来检测收入不平等的基尼系数在五年内提高了1.5%(鲍尔等人,2013年)。

总之,一些政策的好处似乎已经有所夸大,这些政策正是新自由主义议程的一个重要组成部分。在资本开放的情况下,部分资本流动,例如外国直接投资,似乎的确能带来他们所声称的好处。但对于其他人,尤其是短期资本流动,对经济增长没什么好处,而在出现较大动荡和增加危机风险方面,这些政策似乎使得情况迫在眉睫。

在财政整合时,较低的产能和福利以及高失业率方面的短期成本已经被淡化。而一个财政空间充足的国家,面对高负债时,对于允许通过经济的发展从而有机地降低负债率的愿望,总是不得实现。

An adverse loop

Moreover, since both openness and austerity are associated withincreasing income inequality, this distributional effect sets up an adversefeedback loop. The increase in inequality engendered by financial openness andausterity might itself undercut growth, the very thing that the neoliberalagenda is intent on boosting. There is now strong evidence that inequality cansignificantly lower both the level and the durability of growth (Ostry, Berg,and Tsangarides, 2014).

一个怪圈

此外,因为开放和紧缩政策都与收入增长的不平等有关,这种分配效应设置了一个不利的循环。资本开放造成不公平的加剧,资本紧缩本身又可能削弱经济增长,恰好,新自由主义议程的意图就是刺激增长。而有力的证据表明不公平会显著降低经济增长的水平和持续性(Ostry,Berg和Tsangarides,2014年)。

The evidence of the economic damage from inequality suggests thatpolicymakers should be more open to redistribution than they are. Of course,apart from redistribution, policies could be designed to mitigate some of theimpacts in advance—for instance,through increased spending on education and training, which expands equality ofopportunity (so-called predistribution policies). And fiscal consolidation strategies—when they are needed—could bedesigned to minimize the adverse impact on low-income groups. But in somecases, the untoward distributional consequences will have to be remedied after they occur by using taxes and governmentspending to redistribute income. Fortunately, the fear that such policies willthemselves necessarily hurt growth is unfounded (Ostry, 2014).

由不公平所造成的经济损失的表明,政策制定者应该更加注重再分配。当然,除了再分配,可以预先制定一些旨在缓和冲击的政策——例如,通过增加教育和培训的支出,扩大机会的平等(所谓的预分配政策)。而必要时,财政整合策略可以被用来尽量减少对低收入群体带来的不利影响。但在某些情况下,利用税收和政府支出对收入进行再分配后,一些再分配的意外结果必须得到纠正。幸好,担心这样的政策将必然损害经济增长是杞人忧天。(奥斯特里,2014年)。

Finding the balance

These findings suggest a need for a more nuanced view of what theneoliberal agenda is likely to be able to achieve. The IMF, which oversees theinternational monetary system, has been at the forefront of thisreconsideration.

寻找平衡

这些发现表明,对于新自由主义议程的更细致观点的呼唤应该能够实现。负责监督国际货币体系的国际货币基金组织(IMF),早已对重新审议做出了行动。

例如,IMF的前首席经济学家奥利维尔·布兰查德在2010年说:“许多先进的经济体需要一个可信的中期财政整合,而不是像今天一样的财政束缚。”三年后,IMF理事克里斯蒂娜·拉加德说,说我们相信美国国会提出上升该国的债务上限是正确的,“因为目前的重点不是通过野蛮地大幅削减支出来约束经济,因为目前的经济开始复苏。”2015年,IMF建议在欧元区的各国“财政空间应该用来支持投资。”

On capital account liberalization, the IMF’s view has also changed—from one that considered capital controls as almost alwayscounterproductive to greater acceptance of controlstodeal with the volatility of capital flows. The IMF also recognizes that fullcapital flow liberalization is not always an appropriate end-goal, and thatfurther liberalization is more beneficial and less risky if countries havereached certain thresholds of financial and institutional development.

在资本账户自由化方面,IMF的看法也发生了变化——他们原本认为资本管控几乎总是适得其反,如今却在更大程度上接受了它,以应对资本流动的动荡。 IMF还认识到,全面资本流动自由化并不总是一个合适的最终目标,如果国家已达到财政和机构发展的特定阈值,进一步自由化更为有利且风险更低。

智利的新自由主义的开拓经验得到了诺贝尔经济学奖得主弗里德曼的高度赞扬,但现在很多经济学家都向更为细致的观点转变。这些观点来自美国哥伦比亚大学教授约瑟夫·斯蒂格利茨(也是个诺贝尔经济学奖得主)。智利“是市场结合适当监管的一个成功的例子“(2002年)。斯蒂格利茨指出,在早年转向新自由主义期间,智利实行“控制资本的流入,这样他们就不会被淹没,”,例如,泰国,第一次亚洲金融危机爆发的国家,则是十年半以后才这么干的。智利(现在全国避开资本管制),以及其他国家的经验,表明没有固定的章程能够为所有国家的任何时候给予好的结果。这提醒了政策制定者们和一些机构,如国际货币基金组织,制定政策要通过有效的事实证据,绝不是靠自信。

未经允许不得转载:武大金融网 » IMF论文:新自由主义致不平等不稳定

武大金融网

武大金融网